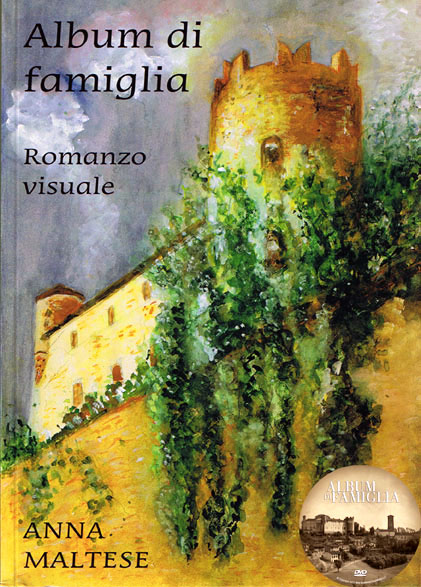

Album di famiglia

Album di famiglia

This enticing family saga unfolds on the background of Italian history from 1870 to 1945. The rich narrative tapestry includes a castle in the countryside near Turin, three women, three generations, and a multitude of minor characters. It brings to the fore individual lives and human predicaments, personal feelings and universal themes. The lives of the three main characters, apparently ordinary, but actually tragic in their inexorable decline, are placed in a coral context that includes: the castle dwellers and the villagers, industrial entrepreneurs and socialist agitators, dive of the silent screen and working girls, American officers in WWI, fascist thugs and victims of the regime, a rogue and an honest prostitute, a star of the Neapolitan varieté, a Russian prince, a descendant of Sir Walton the pirate, a band of partisans, a populist priest, and even a domestic leopard.

The place that inspired the novel is the Castello di Cortanze, which belonged to the author’s family and served as the set for the staging of a video.

The novel is currently being translated into English and will come out in the Spring of 2019.

purchase:

Album di famiglia • Ibs-italia • ediorso.it • amazon-it

Praise for Album di famiglia

“I liked the book immensely, from beginning to end. I found it enticing, evocative, at times heart rendering, at times even comic… The narrative carries you from page to page relentlessly. And now that I’m finished, I want to start again. . .”

“Being the first fiction book by this author, the literary quality is even more striking. I’m not Italian, but I have spent many years in Italy. I’m sure certain scenes from this novel will forever be etched in my mind–scenes that in a few words gave me a picture of fascism more complete that the many volumes written by historians and scholars. Moreover, this book gave me a better knowledge of contemporary Italy than all of the books I have read so far.”

“I found this novel very enticing and certainly worth of a film adaptation. The narrative style is on the same level as that of the best writers of our time, both for the attention to details and for the description of the characters that are finely sketched in their complex psychological dimensions. This novel is a large narrative fresco with visual impact, historical scope and sustained pace, which makes us think of Bertolucci’s cinematic epic 1900. It can also be regarded as a kind of Piedmontese counterpart to The Leopard.”

“It’s a beautiful story. The language is impeccable, not overly literary (unnatural), and not overly conversational (sloppy) either. It’s the perfect language for this story, a saga with its truth filtered through the fabric of narration. It’s the work of a novelist, not of a memoirist.”

“This novel, which has its beginning in family photos, reminds me of the monumental work of Amos Oz, A Story of Love and Darkness. The present novel traces a family saga over three generations, weaving the stories of the many characters with the facts of Italian history. The mythical castle, which provides the visual frame to the novel, serves as the backdrop for the family album which the author used as the literary expedient to begin the narrative.”

“This book brought back sensations that had partly disappeared, and made me forget the particular in favor of a universal world into which everyone can project himself. . . The reference to The Leopard is the first thing that comes to mind because of the analogous situation of an old prominent family experiencing its gradual decline, but also Buddenbrooks by Thomas Mann and The Family Moskat by Isaac Singer.”

↓

Imaging Russia 2000

Imaging Russia 2000

This book incorporates the realities of the 1990s in Russia, focusing on film production, the films themselves, and the socio-political-cultural context. The result is an unfolding story, in which film and facts occupy the same space. The author roams through the narrative, opening fresh fields of vision, and building unexpected montage sequences. She invites the readers to follow her and engage in a challenging interactive game.

The narrative reveals a picture of Russia (with Moscow in the foreground) as the big stage on which the drama unfolded. The author discusses some eighty films made between 1990 and 2000. Many reflect the reality of the present day, either in dramatic or grotesque form. Others reassess the past, placing different spins on various epochs and figures according to the director's ideological orientation. Still others offer escapism into imaginary worlds. The films selected may vary in technical quality and depth of thought; they may be mainstream pictures, or art films. But taken together, they provide an eloquent portrait of Russia, entering the new millennium still in search of its true identity.

PURCHASE:

Amazon • B&N • Indiebound • Google Play • New Academia

Praise for Imaging Russia 2000

“Lawton’s excellent book is both a path-breaking survey of Russian cinema since the fall of the Soviet Union and a lively firsthand account of the faltering first steps of the newly democratic capitalist state.”

“Lawton’s latest book is subversive in both content and form. . . . Superbly researched and vividly written. . . .It is a ‘must read’.”

“Lawton’s book is a first-person journalistic report by a Moscow-based writer living through the decade’s many traumas. Her analyses of the movies are shaded by her personal experience of the post-Soviet situation— the failed coup of August 1991 and the parliamentary crisis of autumn 1993, as well as anecdotes about shopping and apartment hunting—yet they never strike a false note.”

“This melange of emotional diary entries, rough sketches, exhilarating first-person reportage on two coups d’état, abundant flashbacks spotlighting the country’s history, digests of the cinema press, and more, turns out to be a fine way of uncovering the identity of post-Soviet Russia.”

“This book is an engaging read and an informative resource.”

“Anna Lawton’s work on Russian cinema has always been marked by great clarity, good sense, and informative backgrounds and context. In her new book she adds imagination: on-the-ground reports from the new Russia correlated to the films emerging from, and reflecting the new society and its moods.”

↓

Before The Fall

Before The Fall

First Edition - Cambridge Univ. Press, 1992

This is an expanded edition of Kinoglasnost: Soviet Cinema in Our Time (Cambridge University Press, 1992). The book examines the fascinating world of Soviet cinema during the years of glasnost and perestroika—the 1980s. It shows how the reforms that shook the foundations of the Bolshevik state and affected economic and social structures have been reflected in the film industry and in the films the industry produced.

Soviet cinema has always been closely connected with national political reality, challenging the conventions of bourgeois society and educating the people. In this pioneering study, Lawton discusses the restructuring of the main institutions governing the industry; the abolition of censorship; the emergence of independent production and distribution systems; the dismantling of the old bureaucratic structures and the implementation of new initiatives. She also surveys the films that remained unscreened for decades for political reasons, films of the new wave that look at the past to search out the truth, and those that record current social ills or conjure up a disquieting image of the future.

Lawton not only presents a comprehensive picture of the contemporary Soviet film industry, she also analyzes the historical development of the Soviet Union.

PURCHASE:

Amazon • B&N • Indiebound • Google Play • nEW ACADAMIA

Praise for Before The Fall

“What makes Kinoglasnost pre-eminent among current studies of the subject is that sustained attention Lawton pays to changes in the formal organization of Soviet cinema and in the cinema industry.”

“The author constructs a complex, multilayered narrative of a steady and significant movement toward radical change in Soviet society, an account of the growing anxiety and the hope experienced by Russian filmmakers and the intelligentsia.”

“Lawton’s book now stands as a valuable work of history on one aspect of a collapsed system... This remains as a testimony of a fateful moment that has changed the course of history.”

↓

The Red Screen

The Red Screen

This original collection of essays was generated from papers presented at a conference on Soviet Cinema in the US, which gathered together leading Soviet cinema scholars and international specialists for the first time. The conference took place at the Woodrow Wilson Center for International Scholars, in 1986, and was organized by Dr. Anna Lawton, who also edited this volume and wrote an extensive introduction. This collection encompasses seventy years of cinema history from the perspective of twenty academics of different backgrounds and nationalities.

Purchase:

Amazon • B&N • Indiebound • Google Play

↓

Words In Revolution

Words In Revolution

This is the second edition of Russian Futurism Through Its Manifestoes 1912-1928 (Cornell University Pres, 1988). This collection made available for the first time in English the writings of the Russian Futurists, which supplied the theoretical base of their movement. An extensive Introduction by Anna Lawton provides an overview of the movement, and places it in the context of the global international avant garde.

The Introduction highlights the significance of Futurism as an international phenomenon originating in Italy, then sketches the history of Russian Futurism over approximately two decades. Whereas other surveys of Russian Futurism have concentrated either on the prerevolutioinary or the postrevolutionary stages, this Introduction provides a general overview that shows the movement’s basic continuity within change and relates specific moments to the documents included in the collection. This volume also includes an Afterword by Herbert Eagle that deals with the long-lasting legacy of Russian Futurist theories―those of its principles that found a fertile ground in Formalism, Structuralism, and semiotics.

Purchase:

Amazon • Indiebound • New academiA

Praise for Words In Revolution

“This book is a major U.S. contribution toward a better understanding of the avant-garde. It is a useful book not only for scholars of Russian but for those in comparative literature and the history of art and culture as well.”

“Lawton and Eagle skillfully meet the challenge, and their translations well preserve the spirit and general intent found in the original texts. The efforts by Lawton and Eagle provide highly useful documents for English-speakers on the nature of Russian ligerary modernism.”

“The volume produced by Lawton and Eagle is valuable and timely...The editors have shown themselves eminently qualified to pass judgement on the Russian avant-garde.”

↓

Vadim Shershenevich

Vadim Shershenevich

Vadim Shershenevich was one of the most interesting poets and theoreticians of Russian modernism. In his Futurist stage he was notable for his use of Marinetti’s ideas in Russia, and was the only Russian poet to acknowledge the debt to Marinetti. He translated Marinetti’s manifestoes, and the novel Mafarka, il futurista. More importantly, he was founder and leader of Imaginism in Russia, beginning with the first manifesto in 1919 (also signed by Esenin and Marienhof). Lawton’s study contains a general survey of his life and work, plus detailed chapters on Futurism without a Mask, Green Street, and 2 + 2 = 5, the fundamental Imaginist book. The study contains bibliographies of works by and about Shershenevich.

Testimonies from Russian scholars reveal that in Soviet times, when works on the avant garde where removed from circulation, one single copy of this book was held in the Lenin Library in Moscow, and made accessible only to select researchers by special permission. Later the author received several thank you notes from those researchers.